Women who made history

March is Women’s History Month, and across Cyrenians, we’re celebrating some incredible women who’ve made enormous, lasting change to the landscape of homelessness, poverty and social justice in Scotland and beyond. We asked staff from across our 58 services to tell us about some of the women who’ve inspired them.

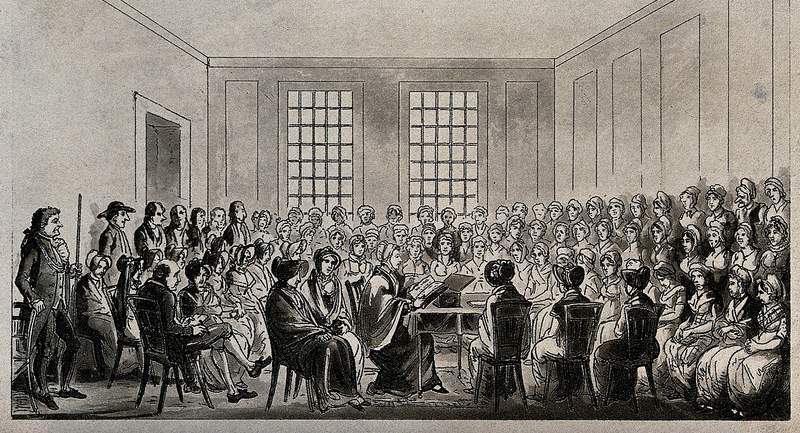

Elizabeth Fry (1780-1845)

Ruth Wilkinson, Relationships Team

Born in England in 1780, Elizabeth Fry is often credited with almost single-handedly driving forward prison reform in Georgian Britain, as well as being a hugely influential voice for social change and for those in power to respect the humanity of people facing poverty and criminalisation. You might recognise Elizabeth Fry from the old English fiver (she was replaced by Winston Churchill in 2016), or from the many social support and reform charities named for her across Europe and North America.

A lifelong Quaker and social activist, from 1816 onwards Fry poured her resources into pushing for better living conditions and a focus on rehabilitation rather than punishment. She was passionately angry about the ways that the horrendous conditions of prisons and the then-common sentences to death or transportation to Australia created a cycle of poverty, abuse and lack of opportunity for people to improve their situation.

As part of her activism, she stayed in prisons across England and Scotland and built up strong relationships with many of the women there, helping some organise within the prison as well as campaigning for legal change. She also introduced skills-development and literacy courses in prisons, and helped people get work on release, and worked to secure regular visits for women in prison, who had often been entirely separated from their families for years. She also organised night shelters in London and started an outreach project across the UK to offer support to families in poverty, and campaigned for the abolition of slavery around the world.

By the time Fry died at 65, she had helped abolish transportation, increase protections and support, and spread prison reform across Europe and America. She was the first woman to give evidence in parliament, provided a lot of foundational evidence for changes in the mental health system as well as the prison system, and established housing and food access projects across the South of England. Most importantly, she did a huge amount to change the conversation around poverty and criminal justice, and to make sure that the humanity and agency of the people at the sharp end of those systems were getting seen by those in power.

By the time Fry died at 65, she had helped abolish transportation, increase protections and support, and spread prison reform across Europe and America. She was the first woman to give evidence in parliament, provided a lot of foundational evidence for changes in the mental health system as well as the prison system, and established housing and food access projects across the South of England. Most importantly, she did a huge amount to change the conversation around poverty and criminal justice, and to make sure that the humanity and agency of the people at the sharp end of those systems were getting seen by those in power.

Octavia Hill (1838-1912)

Colin Waters, SCCR

London and the fate of its poor would have been considerably different if the English social reformer Octavia Hill (1838-1912) had not been active during the second half of the nineteenth century. Although the ranks of her relatives boasted several radical reformers, by the time she reached her teens her once prosperous family had lost its wealth after her father’s business failed and he suffered a breakdown.

Despite receiving no formal education, Hill went on to revolutionise social housing. Realising that landlords frequently didn’t fulfil their obligations to their tenants, and that tenant were ignorant of what they were legally due, Hill decided to become a landlord herself. After securing financial backing, she built and ran a number of houses in London that were clean and safe, with spaces nearby for children to play.

The popularity, not to mention the modest profitability of the housing she ran, proved influential. Mindful of the benefits poor people with access to open spaces enjoyed, Hill campaigned successfully against the development of Hampstead Heath and Parliament Hill Fields. She was also one of the National Trust’s three founding members.

Mary Barbour (1875-1958)

Mhairi MacLennan, People Officer

Mary Barbour, now known as a Scottish political activist, was perhaps not the most obvious campaigner from the get-go. Born in Kilbarchan at the end of the 19th century, she was, until her forties, a ‘typical working-class housewife’. But at age 40, she became the leader of a movement.

Mary Barbour, now known as a Scottish political activist, was perhaps not the most obvious campaigner from the get-go. Born in Kilbarchan at the end of the 19th century, she was, until her forties, a ‘typical working-class housewife’. But at age 40, she became the leader of a movement.

With street meetings, drums, bells and trumpets, she stopped at nothing to bring women out in arms. In 1915, she led the South Govan Women’s Housing Association during the Glasgow rent strikes. She actively organised tenant committees and eviction resistance, so much so that the protestors became known as "Mrs Barbour's Army".

From there, she founded the Women’s Peace Crusade in June 1916; a grassroots socialist movement whose central aim was to spread a ‘people’s peace’, a negotiated peace settlement to World War I, and she later moved into politics in 1920 as a Labour candidate, becoming one of Glasgow’s first woman councillors. She didn’t stop there; she was Chair of the Glasgow Women’s Welfare and Advisory Clinic where she worked with others to establish a clinic – manned only by women nurses and doctors – which became the first site offering advice on birth control in Scotland.

Throughout her career, Barbour worked relentlessly on behalf of the working-class people of her constituency, serving on numerous committees covering the provision of health and welfare services. There is now a statue paying homage to her at Govan Cross, Glasgow.

Throughout her career, Barbour worked relentlessly on behalf of the working-class people of her constituency, serving on numerous committees covering the provision of health and welfare services. There is now a statue paying homage to her at Govan Cross, Glasgow.

Wendy Mitchell (1956-present)

Sylvia Forshaw, OPAL

Currently creating Women’s History, Wendy Mitchell, is a blogger, author and activist who is breaking down barriers for people with a dementia diagnosis. She showed the first symptoms of dementia herself aged 56 while working as an NHS Manager and has been diagnosed with both Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia. Post-diagnosis, Wendy was shocked by the lack of awareness, both in the community and clinical world, so she now campaigns relentlessly to raise awareness and encourage others to embrace her passion for research.

Wendy has written two books: Somebody I Used to Know (a Sunday Times bestseller) and What I Wish People Knew About Dementia; demonstrating how the diagnosis of dementia is not a clear line that a person crosses; they have an illness for which at the moment there is no cure, but they are still one of us. It is the stigma and the loneliness surrounding the disease makes it so difficult to endure.

Wendy now takes part in research, is part of the Three Nations Dementia Working Group, talks at conferences, is a “dementia blogger” offering advice, encouragement and hope to others; wherever she goes, she speaks out about the illness. Dementia “strips away your sense of value” and of having a place and purpose in the world, but talking about it, writing about it, facing the truth, has become her life’s work for as long as she is able to do it.

Read more

How homelessness is a women's issue

Almost half of those registered homeless are women - and many more fly under the radar. What does the epidemic of hidden homelessness mean for women in Scotland?