The role of conflict resolution in preventing homelessness

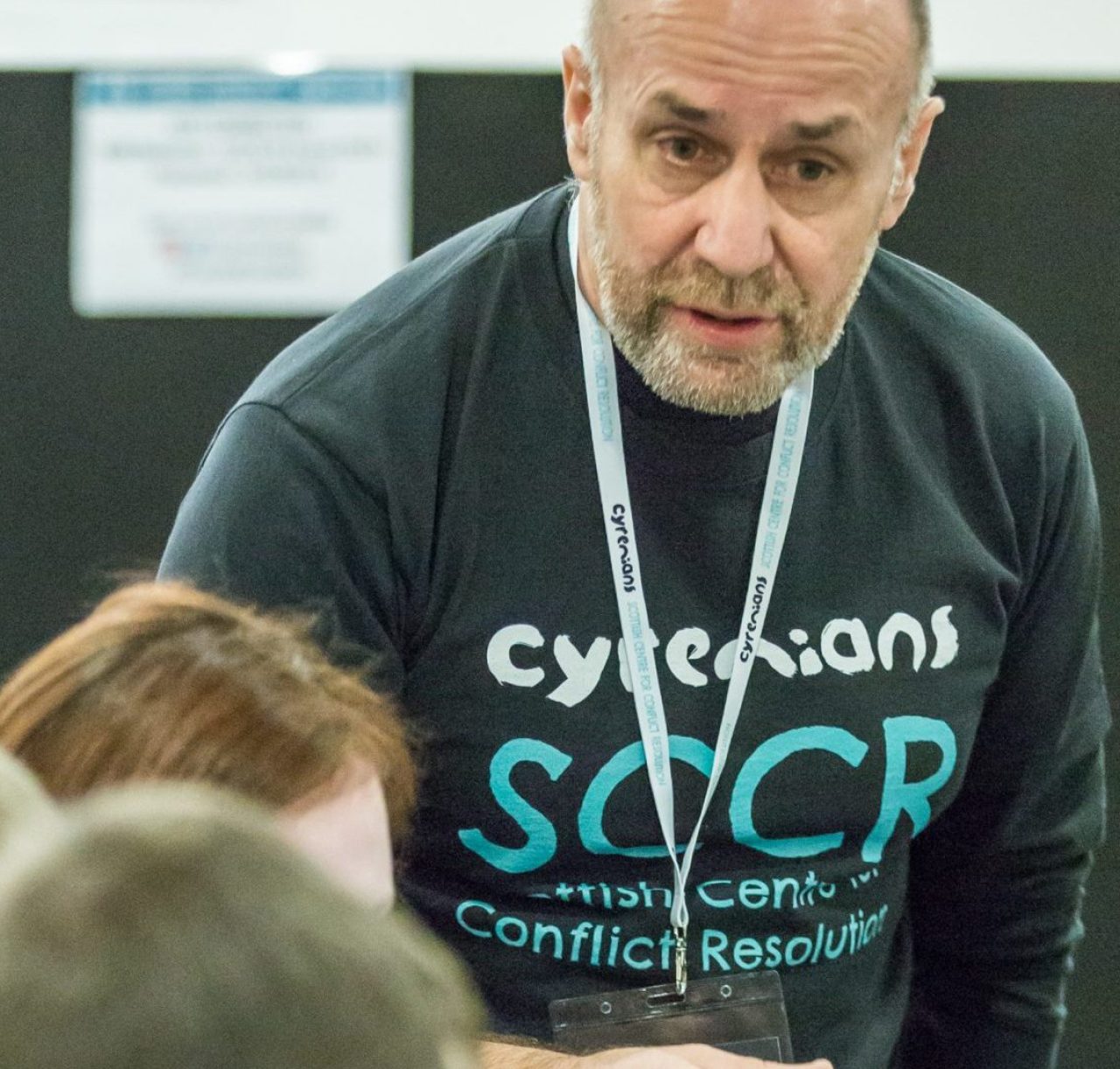

As the Scottish Centre for Conflict Resolution (SCCR) approaches its tenth anniversary. Digital Content and Media Manager Colin Waters reflects on a decade of diffusing conflict and preventing homelessness by keeping families together.

This month, Cyrenians Scottish Centre for Conflict Resolution (SCCR) will mark its tenth anniversary with an exhibition and a reception at the Scottish Parliament. Ten years is a good moment to pause to consider work accomplished and work still to do.

SCCR was set up to reduce the number of young Scots who become homeless each year due to relationship breakdown within families. Since 2014 we’ve worked across all 32 of Scotland’s local authorities to share best practice in resolving conflicts at home. Why? Relationship breakdown caused by family blow-ups remains the leading cause driving youth homelessness.

Over the past decade, SCCR has contributed to a wave of change in Scotland where we’ve moved away from the stigma associated with asking for help towards a culture where parents and carers feel encouraged to seek support. When we started, 6,000 young people per year in Scotland were presenting as homeless. Today, it’s closer to 5,000.

How did SCCR contribute to that cultural change? What we do at SCCR is try to get ahead of that point where mediators are asked to come in and work with families. Built on partnerships with a wide variety of colleagues and collaborators across the country, SCCR focuses on early intervention. We do that by sharing best practice in conflict resolution work via high-quality evidence-led products including online and in-person training events and psychoeducational digital resources.

Conflict within families is a constant, although the reasons behind the conflict might take new forms. When SCCR began, we provided advice on what you might call the perennials of family conflict: money, drugs, schoolwork, and not feeling respected.

Today, though, we’re aware of new kinds of family flashpoints. Some parents and carers may find themselves drawn into arguments when they hear young people echo toxic influencers. Young people might feel enraged by parents and carers who don’t share their sense of urgency over climate change. Then there are caregivers uncertain how to respond to a young person who is neurodiverse or exploring their gender identity.

New causes of conflict should lead to new methods of conflict resolution. Emotional health and wellbeing is an area which has long been a part of SCCR’s offer, but has been coming more to the fore recently. We’ve been approaching conflict resolution by way of bolstering families’ wellbeing, the logic running if people feel happier and healthier they’ll be less likely to fall out with loved ones.

We’ve created a workbook for young people and school packs for teachers that drill down into the science of conflict as a way of explaining why young people and their caregivers argue; the book and the pack form the basis of a new section of our website The Learning Zone, which we’ll launch later this month. In book and online, we look at how changes in the brain during adolescence explain behaviours that cause fall-outs such as risk-taking behaviour and giving more credence to peers than parents. We partner explanations with coping strategies and practical advice on mending relationships.

Can Scotland reduce those youth homelessness figures? That’s our goal for 2034, and we’ll work strategically with other organisations that share our purpose to achieve it. The question isn’t so much ‘What should we do next?’ but one we ask of Scotland: ‘What can we do next together?’

Scottish Centre for Conflict Resolution (SCCR)

Find out more about SCCR

Cyrenians’ Scottish Centre for Conflict Resolution is a National Resource Centre for best practice in conflict resolution, mediation and early intervention work with a particular focus on young people and families.